Men at Forty

Men at forty

Learn to close softly

The doors to rooms they will not be

Coming back to.

At rest on a stair landing,

They feel it

Moving beneath them now like the deck of a ship,

Though the swell is gentle.

And deep in mirrors

They rediscover

The face of the boy as he practices tying

His father’s tie there in secret

And the face of that father,

Still warm with the mystery of lather.

They are more fathers than sons themselves now.

Something is filling them, something

That is like the twilight sound

Of the crickets, immense,

Filling the woods at the foot of the slope

Behind their mortgaged houses.

— Donald Justice

I remember when, years ago, I would read Donald Justice’s poem “Men at Forty” with a kind of anticipatory nostalgia, imagining the sweet melancholy I would feel when I left my thirties behind and joined the legions of men who must, as Justice puts it, “learn to close softly / The doors to rooms they will not be / Coming back to.” I imagined what it would be like to stand before a bathroom mirror and encounter my own image in precisely the manner that the poem describes –

I remember when, years ago, I would read Donald Justice’s poem “Men at Forty” with a kind of anticipatory nostalgia, imagining the sweet melancholy I would feel when I left my thirties behind and joined the legions of men who must, as Justice puts it, “learn to close softly / The doors to rooms they will not be / Coming back to.” I imagined what it would be like to stand before a bathroom mirror and encounter my own image in precisely the manner that the poem describes –

And deep in mirrors

They rediscover

The face of the boy as he practices trying

His father’s tie there in secret

And the face of that father,

Still warm with the mystery of lather

– past and present merging in the very features of my face, a face that would have become more like my father’s than that of the child I had once been. “They are more fathers than sons themselves now,” Justice declares with a kind of forlorn certainty, the scale of time finally tipped from one side to the other, and I imagined that this would of course be true.

It was not true for me, though, when I turned forty. I continued to feel then more son than father, though my father had already died. Now that I am fifty – past fifty, having turned fifty-one – it does indeed seem true, indisputably and inconsolably true. Any childhood photograph of me looks a great deal more like my son than like me, this son who now at seventeen looks more like a man than a boy. And I am startled from time to time when I look in the mirror and feel that I have caught a glimpse, brief and unsettling and spectral, of my father’s weathered face, my startled expression become his, as if he too is surprised to have stumbled upon me in such an otherwise insignificant moment.

It was not true for me, though, when I turned forty. I continued to feel then more son than father, though my father had already died. Now that I am fifty – past fifty, having turned fifty-one – it does indeed seem true, indisputably and inconsolably true. Any childhood photograph of me looks a great deal more like my son than like me, this son who now at seventeen looks more like a man than a boy. And I am startled from time to time when I look in the mirror and feel that I have caught a glimpse, brief and unsettling and spectral, of my father’s weathered face, my startled expression become his, as if he too is surprised to have stumbled upon me in such an otherwise insignificant moment.

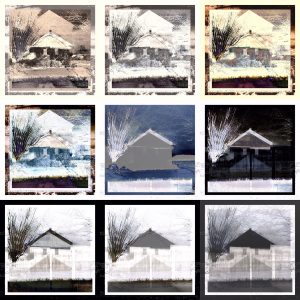

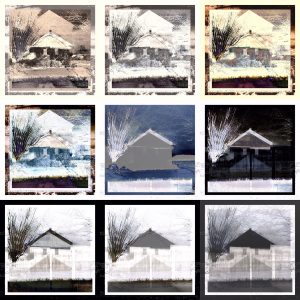

As for the photos I have of my father, they have begun to look – not more like me than him, not that, but more of me, as if they were taken as sly predictions or gentle warnings (to which I was, of course, always much too young to attend) that this is what I would become, the expression I would bear, the lines and folds that I would wear as though they were etched there, as indeed they were in a way, in some act of ritual scarification.

“Something is filling them,” filling these men, Justice goes on to write at his poem’s conclusion,

something

That is like the twilight sound

Of the crickets, immense,

Filling the woods at the foot of the slope

Behind their mortgage houses.

And I used to snicker a little, way back when, at the sweet sad irony of that final line, of the mundane earthly debts and responsibilities – the mortgaged house and all that comes with it: the slope behind it with its inevitably disappointing lawn and the gray mulched flower beds and the scattering of sticks and snake holes and dried leaves – so many inconsequential annoyances and obligations intruding upon that immense and somber and crepuscular sound, the universe’s holy shimmering that the man who has turned forty has just begun to detect.

I don’t snicker any more. I don’t snicker because I know what I didn’t know at thirty or even forty, what even Donald Justice may not have known when he wrote this poem. He was, after all, only just past forty himself when the poem appeared in his 1967 collection Night Light, and so perhaps he was still caught in the sweet pleasures of its sad embrace. I know now, a man at fifty, that even our mundane earthly debts acquire, as time passes, as the scale dips further down, their own spectral grace. We begin to sense that these too – and not just our mortgaged house but the spindly trees we planted, the weedy beds to which we seasonally attend, the dry leaves spilling from the woods’ edge, the sputtering car with its cracked windshield, the flat-tired wheelbarrow, the unwieldy unreliable rake, the vines creeping around porch rails and above doorways, the wasp-infested birdhouse, the nest spilling twigs and cloth from its perch, the carpenter bees’ tunnels of mud and spit, the aching joints, the calloused hands, the cloudy eyes, the stacks of bills in their leather folder, the empty bottles and cans in the kitchen cupboard, the unsprung mousetraps and garbage bags and dryer sheets and wicker baskets and clothes yet to be ironed and nearly spent candles and loose change on the counter – all of this, every bit, are merely the notes composing the grand elegiac hymn, a million and a million more droning voices. They are all, all of them, that twilight sound I hear. It is immense, unceasing, terrifying, as haunting and beautiful a sound as anyone would ever hope to hear.

I don’t snicker any more. I don’t snicker because I know what I didn’t know at thirty or even forty, what even Donald Justice may not have known when he wrote this poem. He was, after all, only just past forty himself when the poem appeared in his 1967 collection Night Light, and so perhaps he was still caught in the sweet pleasures of its sad embrace. I know now, a man at fifty, that even our mundane earthly debts acquire, as time passes, as the scale dips further down, their own spectral grace. We begin to sense that these too – and not just our mortgaged house but the spindly trees we planted, the weedy beds to which we seasonally attend, the dry leaves spilling from the woods’ edge, the sputtering car with its cracked windshield, the flat-tired wheelbarrow, the unwieldy unreliable rake, the vines creeping around porch rails and above doorways, the wasp-infested birdhouse, the nest spilling twigs and cloth from its perch, the carpenter bees’ tunnels of mud and spit, the aching joints, the calloused hands, the cloudy eyes, the stacks of bills in their leather folder, the empty bottles and cans in the kitchen cupboard, the unsprung mousetraps and garbage bags and dryer sheets and wicker baskets and clothes yet to be ironed and nearly spent candles and loose change on the counter – all of this, every bit, are merely the notes composing the grand elegiac hymn, a million and a million more droning voices. They are all, all of them, that twilight sound I hear. It is immense, unceasing, terrifying, as haunting and beautiful a sound as anyone would ever hope to hear.

And I know this, too, I guess, or suspect it – that at sixty I will finally understand that at fifty I had not yet heard the half of it, did not have a clue of the great, magnificent sounds the earth could make, the giant crash of thunder or an axe raised high against the darkening sky to again and again split the wood.

(This post is reprinted from the blog The Admonishing Song.)